Look at the word responsibility—“response-ability”—the ability to choose your response. Highly proactive people recognize that responsibility. They do not blame circumstances, conditions, or conditioning for their behavior. Their behavior is a product of their own conscious choice, based on values, rather than a product of their conditions, based on feeling.

Because we are, by nature, proactive, if our lives are a function of conditioning and conditions, it is because we have, by conscious decision or by default, chosen to empower those things to control us.

In making such a choice, we become reactive. Reactive people are often affected by their physical environment. If the weather is good, they feel good. If it isn’t, it affects their attitude and their performance. Proactive people can carry their own weather with them. Whether it rains or shines makes no difference to them. They are value driven; and if their value is to produce good quality work, it isn’t a function of whether the weather is conducive to it or not.

Reactive people are also affected by their social environment, by the “social weather.” When people treat them well, they feel well; when people don’t, they become defensive or protective. Reactive people build their emotional lives around the behavior of others, empowering the weaknesses of other people to control them.

The ability to subordinate an impulse to a value is the essence of the proactive person. Reactive people are driven by feelings, by circumstances, by conditions, by their environment. Proactive people are driven by values—carefully thought about, selected and internalized values.

Proactive people are still influenced by external stimuli, whether physical, social, or psychological. But their response to the stimuli, conscious or unconscious, is a value-based choice or response.

**

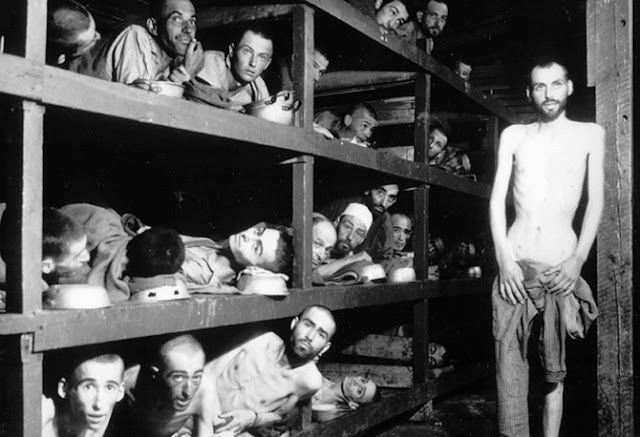

It’s not what happens to us, but our response to what happens to us that hurts us. Of course, things can hurt us physically or economically and can cause sorrow. But our character, our basic identity, does not have to be hurt at all. In fact, our most difficult experiences become the crucibles that forge our character and develop the internal powers, the freedom to handle difficult circumstances in the future and to inspire others to do so as well.

**

Viktor Frankl suggests that there are three central values in life—the experiential, or that which happens to us; the creative, or that which we bring into existence; and the attitudinal, or our response in difficult circumstances such as terminal illness.

My own experience with people confirms the point Frankl makes—that the highest of the three values is attitudinal, in the paradigm or reframing sense. In other words, what matters most is how we respond to what we experience in life.

Difficult circumstances often create paradigm shifts, whole new frames of reference by which people see the world and themselves and others in it, and what life is asking of them. Their larger perspective reflects the attitudinal values that lift and inspire us all.

**

Many people wait for something to happen or someone to take care of them. But people who end up with the good jobs are the proactive ones who are solutions to problems, not problems themselves, who seize the initiative to do whatever is necessary, consistent with correct principles, to get the job done.

**

Businesses, community groups, organizations of every kind—including families—can be proactive. They can combine the creativity and resourcefulness of proactive individuals to create a proactive culture within the organization. The organization does not have to be at the mercy of the environment; it can take the initiative to accomplish the shared values and purposes of the individuals involved.

**

There are some people who interpret “proactive” to mean pushy, aggressive, or insensitive; but that isn’t the case at all. Proactive people aren’t pushy. They’re smart, they’re value driven, they read reality, and they know what’s needed.

Look at Gandhi. While his accusers were in the legislative chambers criticizing him because he wouldn’t join in their Circle of Concern Rhetoric condemning the British Empire for their subjugation of the Indian people, Gandhi was out in the rice paddies, quietly, slowly, imperceptibly expanding his Circle of Influence with the field laborers. A ground swell of support, of trust, of confidence followed him through the countryside. Though he held no office or political position, through compassion, courage, fasting, and moral persuasion he eventually brought England to its knees, breaking political domination of three hundred million people with the power of his greatly expanded Circle of Influence.

**

There are so many ways to work in the Circle of Influence—to be a better listener, to be a more loving marriage partner, to be a better student, to be a more cooperative and dedicated employee. Sometimes the most proactive thing we can do is to be happy, just to genuinely smile. Happiness, like unhappiness, is a proactive choice. There are things, like the weather, that our Circle of Influence will never include. But as proactive people, we can carry our own physical or social weather with us. We can be happy and accept those things that at present we can’t control, while we focus our efforts on the things that we can.

**

For those filled with regret, perhaps the most needful exercise of proactivity is to realize that past mistakes are also out there in the Circle of Concern. We can’t recall them, we can’t undo them, we can’t control the consequences that came as a result.

As a college quarterback, one of my sons learned to snap his wristband between plays as a kind of mental checkoff whenever he or anyone made a “setting back” mistake, so the last mistake wouldn’t affect the resolve and execution of the next play.

The proactive approach to a mistake is to acknowledge it instantly, correct and learn from it. This literally turns a failure into a success. “Success,” said IBM founder T. J. Watson, “is on the far side of failure.”

But not to acknowledge a mistake, not to correct it and learn from it, is a mistake of a different order. It usually puts a person on a self-deceiving, self-justifying path, often involving rationalization (rational lies) to self and to others.

This second mistake, this cover-up, empowers the first, giving it disproportionate importance, and causes far deeper injury to self.

It is not what others do or even our own mistakes that hurt us the most; it is our response to those things. Chasing after the poisonous snake that bites us will only drive the poison through our entire system. It is far better to take measures immediately to get the poison out.

Our response to any mistake affects the quality of the next moment. It is important to immediately admit and correct our mistakes so that they have no power over that next moment and we are empowered again.

**

I would challenge you to test the principle of proactivity for thirty days. Simply try it and see what happens. For thirty days work only in your Circle of Influence. Make small commitments and keep them. Be a light, not a judge. Be a model, not a critic. Be part of the solution, not part of the problem.

Try it in your marriage, in your family, in your job. Don’t argue for other people’s weaknesses. Don’t argue for your own. When you make a mistake, admit it, correct it, and learn from it—immediately. Don’t get into a blaming, accusing mode. Work on things you have control over. Work on you. On be.

Look at the weaknesses of others with compassion, not accusation. It’s not what they’re not doing or should be doing that’s the issue. The issue is your own chosen response to the situation and what you should be doing. If you start to think the problem is “out there,” stop yourself. That thought is the problem.

**

People who exercise their embryonic freedom day after day will, little by little, expand that freedom. People who do not will find that it withers until they are literally “being lived.” They are acting out the scripts written by parents, associates, and society.

We are responsible for our own effectiveness, for our own happiness, and ultimately, I would say, for most of our circumstances.