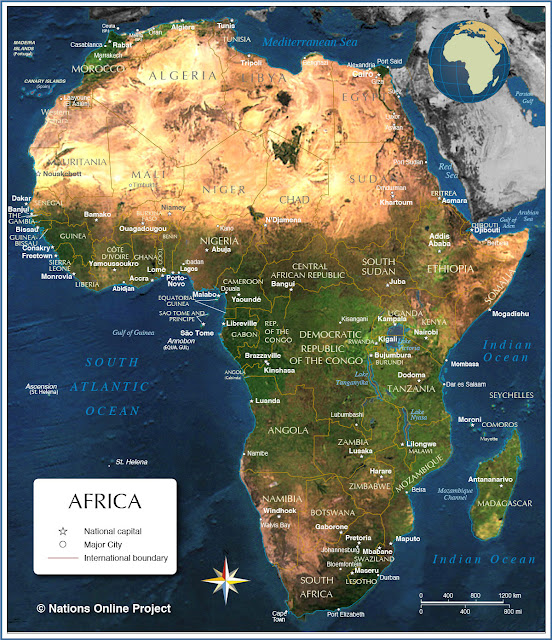

There are now fifty-six countries in Africa. Since the ‘winds of change’ of the independence movement blew through the mid twentieth century, some of the words between the lines have been altered – for example, Rhodesia is now Zimbabwe – but the borders are, surprisingly, mostly intact. However, many encompass the same divisions they did when first drawn, and those formal divisions are some of the many legacies colonialism bequeathed the continent.

The ethnic conflicts within Sudan, Somalia, Kenya, Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, Mali and elsewhere are evidence that the European idea of geography did not fit the reality of Africa’s demographics. There may have always been conflict: the Zulus and Xhosas had their differences long before they had ever set eyes on a European. But colonialism forced those differences to be resolved within an artificial structure – the European concept of a nation state. The modern civil wars are now partially because the colonialists told different nations that they were one nation in one state, and then after the colonialists were chased out a dominant people emerged within the state who wanted to rule it all, thus ensuring violence.

Take, for example, Libya, an artificial construct only a few decades old which at the first test fell apart into its previous incarnation as three distinct geographical regions. In the west it was, in Greek times, Tripolitania (from the Greek tri polis, three cities, which eventually merged and became Tripoli). The area to the east, centred on the city of Benghazi but stretching down to the Chad border, was known in both Greek and Roman times as Cyrenaica. Below these two, in what is now the far south-west of the country, is the region of Fezzan.

Tripolitania was always orientated north and north-west, trading with its southern European neighbours. Cyrenaica always looked east to Egypt and the Arab lands. Even the sea current off the coast of the Benghazi region takes boats naturally eastwards. Fezzan was traditionally a land of nomads who had little in common with the two coastal communities.

This is how the Greeks, Romans and Turks all ruled the area – it is how the people had thought of themselves for centuries. The mere decades-old European idea of Libya will struggle to survive and already one of the many Islamist groups in the east has declared an ‘emirate of Cyrenaica’. While this may not come to pass, it is an example of how the concept of the region originated merely in lines drawn on maps by foreigners.

However, one of the biggest failures of European line-drawing lies in the centre of the continent, the giant black hole known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo – the DRC. Here is the land in which Joseph Conrad set his novel Heart of Darkness, and it remains a place shrouded in the darkness of war. It is a prime example of how the imposition of artificial borders can lead to a weak and divided state, ravaged by internal conflict, and whose mineral wealth condemns it to being exploited by outsiders.

The DRC is an illustration of why the catch-all term ‘developing world’ is far too broad-brush a way to describe countries which are not part of the modern industrialised world. The DRC is not developing, nor does it show any signs of so doing. The DRC should never have been put together; it has fallen apart and is the most under-reported war zone in the world, despite the fact that six million people have died there during wars which have been fought since the late 1990s.

The DRC is neither democratic, nor a republic. It is the second-largest country in Africa with a population of about 81 million, although due to the situation there it is difficult to find accurate figures. It is bigger than Germany, France and Spain combined and contains the Congo Rainforest, second only to the Amazon as the largest in the world.

The people are divided into more than 200 ethnic groups, of which the biggest are the Bantu. There are several hundred languages, but the widespread use of French bridges that gap to a degree. The French comes from the DRC’s years as a Belgian colony (1908–60) and before that, when King Leopold of the Belgians used it as his personal property from which to steal its natural resources to line his pockets. Belgian colonial rule made the British and French versions look positively benign and was ruthlessly brutal from start to finish, with few attempts to build any sort of infrastructure to help the inhabitants. When the Belgians went in 1960 they left behind little chance of the country holding together.

The civil wars began immediately and were later intensified by a blood-soaked walk-on role in the global Cold War. The government in the capital, Kinshasa, backed the rebel side in Angola’s war, thus bringing itself to the attention of the USA, which was also supporting the rebel movement against the Soviet-backed Angolan government. Each side poured in hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of arms.

When the Cold War ended both great powers had less interest in what by then was called Zaire and the country staggered on, kept afloat by its natural resources. The Rift Valley curves into the DRC in its south and east and it has exposed huge quantities of cobalt, copper, diamonds, gold, silver, zinc, coal, manganese and other minerals, especially in Katanga Province.

In King Leopold’s days the world wanted the region’s rubber for the expanding motor car industry; now China buys more than 50 per cent of the DRC’s exports, but still the population lives in poverty. In 2014 the United Nations Human Development Index placed the DRC 186th out of 187 countries it measured. The bottom eighteen countries in that list are all in Africa.

Because it is so resource-rich and so large, everyone wants a bite out of the DRC, which, as it lacks a substantive central authority, cannot really bite back.

The region is also bordered by nine countries. They have all played a role in the DRC’s agony, which is one reason why the Congo wars are also known as ‘Africa’s world war’. To the south is Angola, to the north the Republic of the Congo and the Central African Republic, to the east Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania and Zambia. The roots of the wars go back decades, but the worst of times was triggered by the disaster that hit Rwanda in 1994 and swept westward in its aftermath.

After the genocide in Rwanda the Tutsi survivors and moderate Hutus formed a Tutsi-led government. The killing machines of the Hutu militia, the Interahamwe, fled into eastern DRC but conducted border raids. They also joined with sections of the DRC army to kill the DRC’s Tutsis, who live near the border region. In came the Rwandan and Ugandan armies, backed by Burundi and Eritrea. Allied with opposition militias, they attacked the Interahamwe and overthrew the DRC government. They also went on to control much of the country’s natural wealth, with Rwanda in particular shipping back tons of coltan, which is used in the making of mobile phones and computer chips. However, what had been the government forces did not give up and – with the involvement of Angola, Namibia and Zimbabwe – continued the fight. The country became a vast battleground, with more than twenty factions involved in the fighting.

The wars have killed, at a low estimate, tens of thousands of people, and have resulted in the deaths of another six million due to disease and malnutrition. The UN estimates that almost 50 per cent of the victims have been children aged under five.

In recent years the fighting has died down, but the DRC is home to the world’s most deadly conflict since the Second World War and still requires the UN’s largest peacekeeping mission to prevent full-scale war from breaking out again. Now the job is not to put Humpty Dumpty together again, because the DRC was never whole. It is simply to keep the pieces apart until a way can be found to join them sensibly and peacefully. The European colonialist created an egg without a chicken, a logical absurdity repeated across the continent and one that continues to haunt it.

p

le of how the concept of the region originated merely in lines drawn on maps by foreigners.