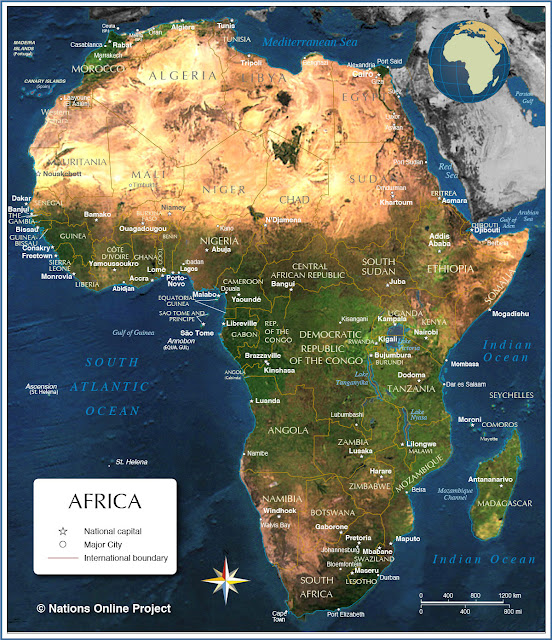

Africa’s coastline? Great beaches, really, really lovely beaches, but terrible natural harbours. Rivers? Amazing rivers, but most of them are rubbish for actually transporting anything, given that every few miles you go over a waterfall. These are just two in a long list of problems which help explain why Africa isn’t technologically or politically as successful as Western Europe or North America.

There are lots of places that are unsuccessful, but few have been as unsuccessful as Africa, and that despite having a head start as the place where Homo sapiens originated about 200,000 years ago. As that most lucid of writers, Jared Diamond, put it in a brilliant National Geographic article in 2005, ‘It’s the opposite of what one would expect from the runner first off the block.’ However, the first runners became separated from everyone else by the Sahara Desert and the Indian and Atlantic oceans. Almost the entire continent below the Sahara developed in isolation from the Eurasian land mass, where ideas and technology were exchanged from east to west, and west to east, but not north to south.

**

Given that Africa is where humans originated, we are all African. However, the rules of the race changed c. 8000 BCE when some of us, who’d wandered off to places such as the Middle East and around the Mediterranean region, lost the wanderlust, settled down, began farming and eventually congregated in villages and towns.

But back south there were few plants willing to be domesticated, and even fewer animals. Much of the land consists of jungle, swamp, desert or steep-sided plateau, none of which lend themselves to the growing of wheat or rice, or sustaining herds of sheep. Africa’s rhinos, gazelles and giraffes stubbornly refused to be beasts of burden – or as Diamond puts it in a memorable passage, ‘History might have turned out differently if African armies, fed by barnyard-giraffe meat and backed by waves of cavalry mounted on huge rhinos, had swept into Europe to overrun its mutton-fed soldiers mounted on puny horses.’ But Africa’s head start in our mutual story did allow it more time to develop something else which to this day holds it back: a virulent set of diseases, such as malaria and yellow fever, brought on by the heat and now complicated by crowded living conditions and poor healthcare infrastructure. This is true of other regions – the subcontinent and South America, for example – but sub-Saharan Africa has been especially hard hit, for example by the HIV virus, and has a particular problem because of the prevalence of the mosquito and the Tsetse fly.

Most of the continent’s rivers also pose a problem, as they begin in high land and descend in abrupt drops which thwart navigation. For example, the mighty Zambezi may be Africa’s fourth-longest river, running for 1,600 miles, and may be a stunning tourist attraction with its white-water rapids and the Victoria Falls, but as a trade route it is of little use. It flows through six countries, dropping from 4,900 feet to sea level when it reaches the Indian Ocean in Mozambique. Parts of it are navigable by shallow boats, but these parts do not interconnect, thus limiting the transportation of cargo.

Unlike in Europe, which has the Danube and the Rhine, this drawback has hindered contact and trade between regions – which in turn affected economic development, and hindered the formation of large trading regions. The continent’s great rivers, the Niger, the Congo, the Zambezi, the Nile and others, don’t connect and this disconnection has a human factor. Whereas huge areas of Russia, China and the USA speak a unifying language which helps trade, in Africa thousands of languages exist and no one culture emerged to dominate areas of similar size. Europe, on the other hand, was small enough to have a ‘lingua franca’ through which to communicate, and a landscape that encouraged interaction.

Even had technologically productive nation states arisen, much of the continent would still have struggled to connect to the rest of the world because the bulk of the land mass is framed by the Indian and Atlantic oceans and the Sahara Desert. The exchange of ideas and technology barely touched sub-Saharan Africa for thousands of years. Despite this, several African empires and city states did arise after about the sixth century CE: for example the Mali Empire (thirteenth–sixteenth century), and the city state of Great Zimbabwe (eleventh– fifteenth century), the latter in land between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers.

However, these and others were isolated to relatively small regional blocs, and although the myriad cultures which did emerge across the continent may have been politically sophisticated, the physical landscape remained a barrier to technological development: by the time the outside world arrived in force, most had yet to develop writing, paper, gunpowder or the wheel.