Tuesday, February 22, 2022

Ten Global Trends

You can't fix what is wrong in the world if you don't know what's actually happening. In this book, straightforward charts and graphs, combined with succinct explanations, will provide you with easily understandable access to the facts that busy people need to know about how the world is really faring.

Polls show that most smart people tend to believe that the state of the world is getting worse rather than better. Consider a 2016 survey by the global public opinion company YouGov that asked folks in 17 countries, "All things considered, do you think the world is getting better or worse, or neither getting better nor worse?” Fifty-eight percent of respondents thought that the world is getting worse, and 30 percent said that it is doing neither. Only 11 percent thought that things are getting better. In the United States, 65 percent of Americans thought that the world is getting worse, and 23 percent said neither. Only 6 percent of Americans responded that the world is getting better.

This dark view of the prospects for humanity and the natural world is, in large part, badly mistaken. We demonstrate it in these pages using uncontroversial data taken from official and scientific sources.

Of course, some global trends are negative. As Harvard University psychologist Steven Pinker says: "It's essential to realize that progress does not mean that everything gets better for everyone, everywhere, all the time. That would be a miracle, that wouldn't progress." For example, man made climate change arising largely from increasing atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide released from burning fossil fuels could become a significant problem for humanity during this century. The spread of plastic marine debris is a big and growing concern. Many wildlife populations are declining, and tropical forest area continues shrinking. In addition, far too many people are still malnourished and dying in civil and sectarian conflicts around the globe. And, of course, the world is afflicted by the current coronavirus pandemic.

However, many of the global trends we describe are already helping redress such problems. For example, the falling price of renewable energy sources incentivize the switch away from fossil fuels. Moreover, increasingly abundant agriculture is globally reducing the percentage of people who are hungry while simultaneously freeing up land so that forests are now expanding in much of the world. And unprecedentedly rapid research has significantly advanced testing, tracking, and treatment technologies to ameliorate the coronavirus contagion.

PSYCHOLOGICAL GLITCHES MISLEAD YOU

So why do so many smart people wrongly believe that all things considered, the world is getting worse?

Way back in 1965, Johan Galtung and Mari Holmboe Ruge, from the Peace Research Institute Oslo, observed, "There is a basic asymmetry in life between the positive, which is difficult and takes time, and the negative, which is much easier and takes less time-compare the amount of time needed to bring up and socialize an adult person and the amount of time need ed to kill him in an accident, the amount of time needed to build a house and to destroy it in a fire, to make an airplane and to crash it, and so on." News is bad news; steady progress is not news.

Smart people especially seek to be well informed and so tend to be voracious consumers of news. Since journalism focuses on dramatic things and events that go wrong, the nature of news thus tends to mislead readers and viewers into thinking that the world is in worse shape than it really is. This mental shortcut causes many of us to confuse what comes easily to mind with what is true; it was first identified in 1973 by behavioral scientists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman as the "availability bias." Another reason for the ubiquity of mistaken gloom derives from a quirk of our evolutionary psychology. A Stone Age man hears a rustle in the grass. Is it the wind or a lion? If he assumes it's the wind and the rustling turns out to be a lion, then he's not an ancestor. We are the descendants of the worried folks who tended to assume that all rustles in the grass were dangerous predators and not the wind. Because of this instinctive negativity bias, most of us attend far more to bad rather than to good news. The upshot is that we are again often misled into thinking that the world is worse than it is.

"Judgment creep" is yet another explanation for the prevalence of wrong-headed pessimism. We are misled about the state of the world because we have a tendency to continually raise our threshold for success as we make progress, argue Harvard University psychologist Daniel Gilbert and his colleagues. "When problems become rare, we count more things as problems. Our studies suggest that when the world gets better, we become harsher critics of it, and this can cause us to mistakenly conclude that it hasn't actually gotten better at all," explains Gilbert. "Progress, it seems, tends to mask itself." Social, economic, and environmental problems are being judged intractable because reductions in their prevalence lead people to see more of them. More than 150 years ago, political scientist Alexis de Tocqueville noted a similar phenomenon as societies progress, one that has since been called the Tocqueville effect.

What, though, accounts for progress?

Some smart folk who acknowledge that considerable social, economic, and environmental progress has been made still worry that progress will not necessarily continue.

"Human beings still have the capacity to mess it all up. And it may be that our capacity to mess it up is growing," asserted Cambridge University political scientist David Runciman in a July 2017 Guardian article. He added: "For people to feel deeply uneasy about the world we inhabit now, despite all these indicators pointing up, seems to me reasonable, given the relative instability of the evidence of this progress, and the [unpredictability] that overhangs it. Everything really is pretty fragile."

Runciman is not alone. The worry that civilization is just about to go over the edge of a precipice has a long history. After all, many earlier civilizations and regimes have collapsed, including the Babylonian, Roman, Tang, and Mayan Empires, and more recently the Ottoman and Soviet Empires.

In their 2012 book, Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty, economists Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson persuasively outline reasons for the exponential improvement in human well-being that started about two centuries ago.

They begin by arguing that since the Neolithic agricultural revolution, most societies have been organized around "extractive" institutions-political and economic systems that funnel resources from the masses to the elites.

In the 18th century, some countries including Britain and many of its colonies-shifted from extractive to inclusive institutions. "Inclusive economic institutions that enforce property rights, create a level playing field, and encourage investments in new technologies and skills are more conducive to economic growth than extractive economic institutions that are structured to extract resources from the many by the few," they write. "Inclusive economic institutions are in turn supported by, and support, inclusive political institutions," which "distribute political power widely in a pluralistic manner and are able to achieve some amount of political centralization so as to establish law and order, the foundations of secure property rights, and an inclusive market economy." Inclusive institutions are similar to one another in their respect for individual liberty. They include democratic politics, strong private property rights, the rule of law, enforcement of contracts, freedom of movement, and a free press. Inclusive institutions are the basis of the technological and entrepreneurial innovations that produced a historically unprecedented rise in living standards in those countries that embraced them, including the United States, Japan, and Australia as well as the countries in Western Europe. They are qualitatively different from the extractive institutions that preceded them.

The spread of inclusive institutions to more and more countries was uneven and occasionally reversed. Those advances and in the University of Illinois at Chicago economist Deirdre Mc Closkey's view, the key role played by major ideological shifts resulted in what McCloskey calls the "great enrichment," which boosted average incomes thirtyfold to a hundredfold in those countries where they have taken hold.

The examples of societal disintegration cited earlier, whether Roman, Tang, or Soviet, occurred in extractive regimes. Despite crises such as the Great Depression, there are no examples so far of countries with long-established inclusive political and economic institutions suffering similar collapses.

In addition, confrontations between extractive and inclusive regimes, such as World War II and the Cold War, have generally been won by the latter. That suggests that liberal free-market democracies are resilient in ways that enable them to forestall or rise above the kinds of shocks that destroy brittle extractive regimes.

If inclusive liberal institutions can continue to be strengthened and further spread across the globe, the auspicious trends documented in this book will extend their advance, and those that are currently negative will turn positive. By acting through inclusive institutions to increase knowledge and pursue technological progress, past generations met their needs and hugely increased the ability of our generation to meet our needs. We should do no less for our own future generations. That is what sustainable development looks like.

Saturday, February 12, 2022

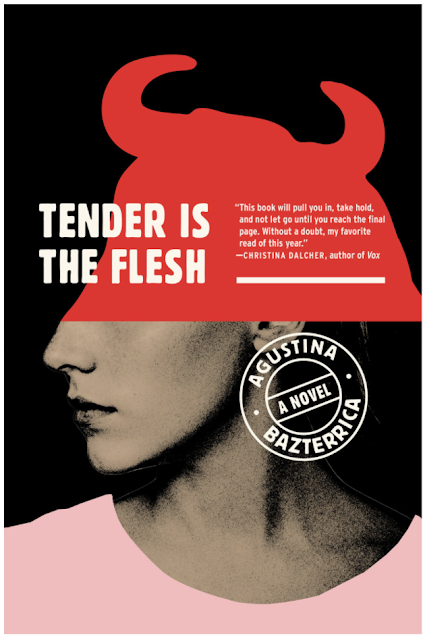

We devour each other

It all started with my brother, to whom I dedicated the novel. The idea arose from the long evenings I spent at his restaurant Ocho Once in Buenos Aires. Gonzalo Bazterrica is a chef and he works with organic food; but above all, he is a conscious food researcher and, through his cooking and his research I could understand what Hippocrates meant by: “Let food be thy medicine and let medicine be thy food”.

Thanks to my own reading on the topic I gradually changed my diet and I stopped eating meat. When I did, a veil was drawn, and my view of meat consumption was completely changed. To me, a steak is now a piece of a corpse. One day I was walking by a butcher’s shop and all I saw were bodies of animals hanging down and I thought, “Why can’t those be human corpses? After all we are animals, we are flesh.” And that’s how the idea for the novel emerged.

I wanted to write about how, in the near future, cannibalism could be legalised, but I needed a story. And the plot that I imagined is this: there is a so-called virus affecting animals rendering them inedible and cannibalism becomes legal. Humans start being butchered in meat-processing plants. The protagonist runs a meat-processing plant and is gifted a female to butcher or raise. That is, he has a naked woman in his possession. I won’t give away what happens later.

The creative process was visceral, compulsive; but since I am obsessive, there was a preparation process. I had the story quite clear in my head before sitting down to write it. What I did first was research. I read a formidable amount of manuals, instructions, fiction material and essays on cannibalism, on meat industry operations and animal rights. I also watched movies, documentaries and videos. That was the hardest part of the process, the one most difficult to face due to the violence of the imagery. Seeing how chickens get their beaks cut off so they won’t peck each other due to overcrowding is disturbing. Seeing how a wild animal is skinned alive is heartbreaking.

Although my book contains clear criticism of the meat industry, I also wrote the novel because I have always believed that in our capitalist, consumerist society, we devour each other. We phagocyte each other in many ways and in varying degrees: human trafficking, war, precarious work, modern slavery, poverty, gender violence are just a few examples of extreme violence.

Objectivising and depersonalising others allows us to remove them from the category of human being (our equal) and place them in the category of a mere “other”, whom we can be violent to, kill, discriminate against, hurt, etc. One clear example: when we allow a 12-year-old girl to work as a prostitute, it shows that there is a part of society that is indifferent, uninterested in that situation, and that another huge part validates it because it benefits them and in the middle of all that there is this little girl being consumed by everyone.

Hannah Arendt, says in her book Eichmann in Jerusalem, whose subtitle is: “A report on the banality of evil”, that the extermination of Jews in Germany and other European countries was not down to the pure evil in Nazi rulers, but to society’s indifference. This massacre, executed by bureaucrats, would not have been possible without the indifference of “good” citizens.

Thus, we devour each other because we are generally blind to our kinship with others. When faced with their suffering, we look the other way. And we do the same with other sentient beings. It may sound exaggerated, for sure. But to many Argentinians, a meat dish is not seen as a being, but merely as protein. In my country, meat is part of our national identity. Barbecues are basically considered sacred rites. As if they were part of a religious celebration, on Sundays, many Argentinians place pieces of meat on their grills and meet with friends to eat it. The latest official study of 2018 found that the average Argentine eats 118kg of meet a year. There are 45 million Argentinians. That is a staggering amount of meat.

Having said this, I want to make clear that I am not on a crusade to convert carnivores to vegetarianism. I never meant to write a vegan pamphlet. I tried to write the best novel I could possibly write, without trying to convince anyone of anything because, in my opinion, fanaticism is another form of violence.

Despite the fact that I actually am a vegetarian, meat is also part of my identity and I am part of a society that eats meat and unflinchingly accepts animal cruelty with the same brutal indifference shown towards vulnerable groups such as the poor, indigenous populations and women. We are a country that also murders its women. There is one femicide every 18 hours and there are no statistics for deaths related to clandestine abortions since in Argentina it is a crime.

My identity is also pierced, modelled and built by heteronormativity, the deep patriarchy. That boundless weave of oppression that has language as one of its greatest accomplices and supporters. As Heidegger says: “language is the house of being”.

Language gives us an identity; it speaks of who we are. In my country, in my language, a language I share with 22 other nations and 572 million people, we say “dog” – perro – to speak about man’s best friend. When we use the feminine noun perra it becomes synonyms with puta (whore). When we speak about someone who is daring – atrevido – we are talking about a fearless man. When we utter the feminine form atrevida we are referring to a puta (whore). The synonyms we use in Spanish for puta are many (101, to be precise), but there is no negative equivalent to talk about a man who has sex with many women. Because using the masculine form puto constitutes an insult to refer to a homosexual man. Men who have sex with lots of women are considered desirable. There is no derogative word to define them and that is a clear sign of the social construction that is patriarchy.

That is why in Tender is the Flesh I tried to work carefully with language. Creating a new matrix requires new words, new ways of naming new things, like when they call a human that is bred for consumption a “product”. But I also worked with silence, with the unwritten word, which is another form of cannibalism because by not saying certain things we become complicit, we help build and perpetuate that reality. When we do not talk about femicide, for example, we give room to impunity, to thinking that women’s lives are worthless. By naming acts of violence and understanding them, we give them entity and can work towards preventing them.

Language is energy. As Peruvian author César Calvo said: “whoever pronounces words sets potentialities into motion”. Through this book, through these words, I wish to move the energy of a non-violent, caring culture, to think of a world where we respect differences with equal rights, a world where one woman isn’t killed every 18 hours in acts of gender-based violence, a world where symbolic or real cannibalism is just fiction.

Tender is the flesh

He had to fire Ency because someone who’s been broken can’t be fixed. He did speak to Krieg and make sure he arranged and paid for psychological care. But within a month, Ency had shot himself. His wife and kids had to leave the neighborhood, and since then Manzanillo has looked at him with genuine hatred. He respects Manzanillo for it. He thinks it’ll be cause for concern when the man stops looking at him this way, when the hatred doesn’t keep him going any longer. Because hatred gives one strength to go on; it maintains the fragile structure, it weaves the threads together so that emptiness doesn’t take over everything. He wishes he could hate someone for the death of his son. But who can he blame for a sudden death? He tried to hate God, but he doesn’t believe in God. He tried to hate all of humanity for being so fragile and ephemeral, but he couldn’t keep it up because hating everyone is the same as hating no one. He also wishes he could break like Ency, but his collapse never comes.

Tuesday, February 1, 2022

O Zât

“O Zât, pek büyük ve bütün zamanları ve mekânları kapsayan, ezelden ebede uzanan bir davada bulunuyor. Allah ile konuştuğunu, yirmi üç yıl boyunca O’ndan âyetler, sûreler aldığını, O’nun adına hareket ettiğini söylüyor. Yalnız bunları söylemekle kalmıyor. Kimsenin görmediği gaybî meselelerden; pek çoğu zamanla ortaya çıkacak ve çıkmış kâinat gerçeklerinden; kâinatın yaratılış safhalarından; insanın ta başta her bir insanın anne karnında nasıl ve hangi safhalardan geçerek yaratıldığından; insana hilâfet vazifesi verilmesinden; melekler, insan ve şeytan arasında geçen hadiselerden; Hz. Allah’ın İsimleri’nden, Sıfatla-rı’ndan ve icraatından; varlığın tabakaları ve her bir tabakanın hususiyetlerinden; Ruh, melekler ve cinler diye görünmez varlıklardan; geçmiş zamanlardan, yani binlerce sene geriye giden tarihlerden ve bu tarihlerde yaşayan topluluklardan; yakın ve uzak gelecekten; dünyanın yıkılıp ebedî ve yepyeni bir âlemin kurulacağından bahsediyor. Bunlardan bahsederken de hiçbir zaman “Böyle düşünüyorum, sanırım, tahmin ederim.” gibi ifadeler kullanmıyor; bunları kullanmak şöyle dursun, çok kesin, çok net konuşuyor; gelecekten bahsederken bile âdeta olmuş gibi sözediyor. Ve aradan geçen ondört asır içinde gelecekle ilgili verdiği yüzlerce haberin pek çoğu aynen gerçekleşmiş bulunuyor. Bütün bunları tek bir zaman diliminde tek bir topluluk önünde söylemiyor. Bütün zamanlara ve bütün topluluklara hitap ederek söylüyor. Sıradan bir insan bile basit bir meselede küçük bir topluluk önünde yalana dayalı bir iddiada bulunmaktan çekinir. Fakat bu Zât, son derece büyük bir davayı ve sözünü ettiğimiz meseleleri bütün zamanlar, mekânlar ve topluluklar önünde hiç çekinmeden, kesin bir dille ve pervasızca dile getiriyor. Böyle bir Zât’ın, söylediklerinden emin olmaksızın kendinden ve hevasından konuşması mümkün müdür? Bir yanlışı, bir yalanı ortaya çıktığında bütün iddialarının ve davasının yıkılıp gideceği açıkken, her şeyi bilen Allah tarafından konuşturulmadıkça bu kadar meselede bu kadar kesin ve net konuşması mümkün müdür?”