It all started with my brother, to whom I dedicated the novel. The idea arose from the long evenings I spent at his restaurant Ocho Once in Buenos Aires. Gonzalo Bazterrica is a chef and he works with organic food; but above all, he is a conscious food researcher and, through his cooking and his research I could understand what Hippocrates meant by: “Let food be thy medicine and let medicine be thy food”.

Thanks to my own reading on the topic I gradually changed my diet and I stopped eating meat. When I did, a veil was drawn, and my view of meat consumption was completely changed. To me, a steak is now a piece of a corpse. One day I was walking by a butcher’s shop and all I saw were bodies of animals hanging down and I thought, “Why can’t those be human corpses? After all we are animals, we are flesh.” And that’s how the idea for the novel emerged.

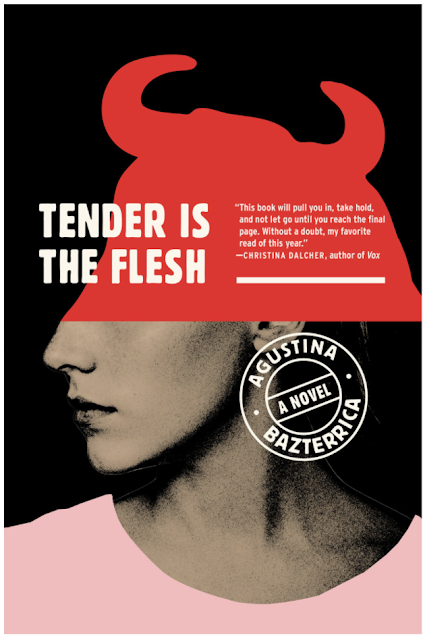

I wanted to write about how, in the near future, cannibalism could be legalised, but I needed a story. And the plot that I imagined is this: there is a so-called virus affecting animals rendering them inedible and cannibalism becomes legal. Humans start being butchered in meat-processing plants. The protagonist runs a meat-processing plant and is gifted a female to butcher or raise. That is, he has a naked woman in his possession. I won’t give away what happens later.

The creative process was visceral, compulsive; but since I am obsessive, there was a preparation process. I had the story quite clear in my head before sitting down to write it. What I did first was research. I read a formidable amount of manuals, instructions, fiction material and essays on cannibalism, on meat industry operations and animal rights. I also watched movies, documentaries and videos. That was the hardest part of the process, the one most difficult to face due to the violence of the imagery. Seeing how chickens get their beaks cut off so they won’t peck each other due to overcrowding is disturbing. Seeing how a wild animal is skinned alive is heartbreaking.

Although my book contains clear criticism of the meat industry, I also wrote the novel because I have always believed that in our capitalist, consumerist society, we devour each other. We phagocyte each other in many ways and in varying degrees: human trafficking, war, precarious work, modern slavery, poverty, gender violence are just a few examples of extreme violence.

Objectivising and depersonalising others allows us to remove them from the category of human being (our equal) and place them in the category of a mere “other”, whom we can be violent to, kill, discriminate against, hurt, etc. One clear example: when we allow a 12-year-old girl to work as a prostitute, it shows that there is a part of society that is indifferent, uninterested in that situation, and that another huge part validates it because it benefits them and in the middle of all that there is this little girl being consumed by everyone.

Hannah Arendt, says in her book Eichmann in Jerusalem, whose subtitle is: “A report on the banality of evil”, that the extermination of Jews in Germany and other European countries was not down to the pure evil in Nazi rulers, but to society’s indifference. This massacre, executed by bureaucrats, would not have been possible without the indifference of “good” citizens.

Thus, we devour each other because we are generally blind to our kinship with others. When faced with their suffering, we look the other way. And we do the same with other sentient beings. It may sound exaggerated, for sure. But to many Argentinians, a meat dish is not seen as a being, but merely as protein. In my country, meat is part of our national identity. Barbecues are basically considered sacred rites. As if they were part of a religious celebration, on Sundays, many Argentinians place pieces of meat on their grills and meet with friends to eat it. The latest official study of 2018 found that the average Argentine eats 118kg of meet a year. There are 45 million Argentinians. That is a staggering amount of meat.

Having said this, I want to make clear that I am not on a crusade to convert carnivores to vegetarianism. I never meant to write a vegan pamphlet. I tried to write the best novel I could possibly write, without trying to convince anyone of anything because, in my opinion, fanaticism is another form of violence.

Despite the fact that I actually am a vegetarian, meat is also part of my identity and I am part of a society that eats meat and unflinchingly accepts animal cruelty with the same brutal indifference shown towards vulnerable groups such as the poor, indigenous populations and women. We are a country that also murders its women. There is one femicide every 18 hours and there are no statistics for deaths related to clandestine abortions since in Argentina it is a crime.

My identity is also pierced, modelled and built by heteronormativity, the deep patriarchy. That boundless weave of oppression that has language as one of its greatest accomplices and supporters. As Heidegger says: “language is the house of being”.

Language gives us an identity; it speaks of who we are. In my country, in my language, a language I share with 22 other nations and 572 million people, we say “dog” – perro – to speak about man’s best friend. When we use the feminine noun perra it becomes synonyms with puta (whore). When we speak about someone who is daring – atrevido – we are talking about a fearless man. When we utter the feminine form atrevida we are referring to a puta (whore). The synonyms we use in Spanish for puta are many (101, to be precise), but there is no negative equivalent to talk about a man who has sex with many women. Because using the masculine form puto constitutes an insult to refer to a homosexual man. Men who have sex with lots of women are considered desirable. There is no derogative word to define them and that is a clear sign of the social construction that is patriarchy.

That is why in Tender is the Flesh I tried to work carefully with language. Creating a new matrix requires new words, new ways of naming new things, like when they call a human that is bred for consumption a “product”. But I also worked with silence, with the unwritten word, which is another form of cannibalism because by not saying certain things we become complicit, we help build and perpetuate that reality. When we do not talk about femicide, for example, we give room to impunity, to thinking that women’s lives are worthless. By naming acts of violence and understanding them, we give them entity and can work towards preventing them.

Language is energy. As Peruvian author César Calvo said: “whoever pronounces words sets potentialities into motion”. Through this book, through these words, I wish to move the energy of a non-violent, caring culture, to think of a world where we respect differences with equal rights, a world where one woman isn’t killed every 18 hours in acts of gender-based violence, a world where symbolic or real cannibalism is just fiction.