The better you are at math, the more money seems to influence your satisfaction

Your grade school math teacher probably told you that being good at math would be very important to your grownup self. But maybe the younger you didn’t believe that at the time. A lot of research, though, has shown that your teacher was right.

We are two researchers who study decision-making and how it relates to wealth and happiness. In a study published in November 2021, we found that, in general, people who are better at math make more money and are more satisfied with their lives than people who aren’t as mathematically talented. But being good at math seems to be a double-edged sword. Although math-proficient people are very satisfied when they have high incomes, they are more dissatisfied, compared to those who aren’t as good at math, when they don’t make a lot of money.

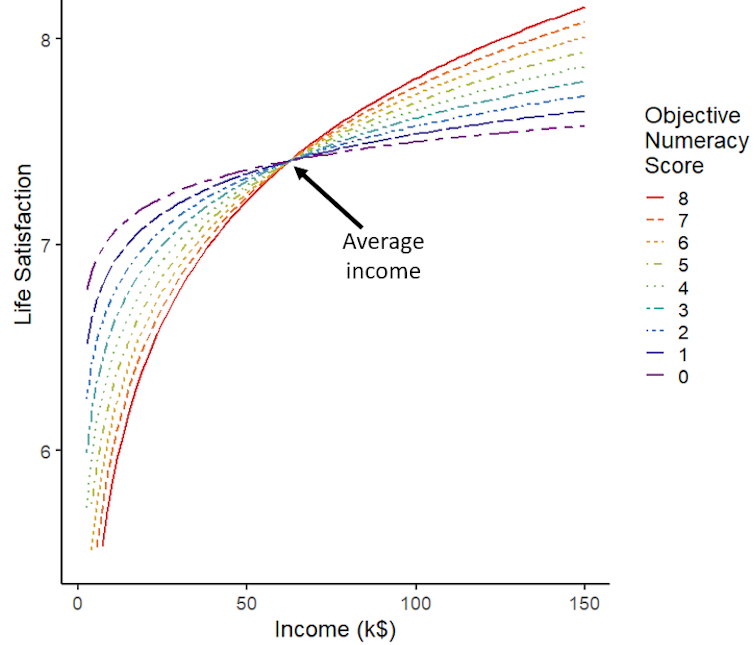

Many researchers have suggested that more money only increases life satisfaction and happiness up to a certain point. Our research modifies this idea by showing that satisfaction derived from income relates strongly to how good a person is at math.

A math and happiness test

We investigated the relationship between math ability, income and life satisfaction, using surveys sent to 5,748 diverse Americans as part of the Understanding America Study.

The study included two questions and one test relevant to our research. One question asked participants about their household yearly income. Another one asked respondents to rate how satisfied they are with their lives on a scale of zero to 10.

Finally, people answered eight math questions that varied in difficulty to get a sense of their math skills. For example, one of the moderately difficult questions was: “Jerry received both the 15th highest and the 15th lowest mark in the class. How many students are in the class?” The correct answer is 29 students.

We then combined the results to see how they all related to one another.

Math skills and income also are tied to level of education, so, in our analyses, we controlled for education, verbal intelligence, personality traits and other demographics.

Connecting math skills to income and satisfaction

On average, the better a person was at math, the more money they made. For every one additional right answer on the eight-question math test, people reported an average of $4,062 more in annual income.

Imagine you have two people with the same level of education, one of whom answered none of the math questions correctly and the other answered all of them correctly. Our research predicts that the person who answered all of the questions correctly will earn about $30,000 more each year.

The survey also showed that people who are better at math were, on average, also more satisfied with their lives than those with lower math ability. This finding agrees with a lot of other research and suggests that income influences life satisfaction.

But prior research has shown that the relationship between income and satisfaction is not as straightforward as “more money equals greater happiness.” It turns out that how satisfied a person is with their income often depends on how they feel it compares to other people’s incomes.

Other research has also shown that people who are better at math tend to make more numerical comparisons in general than those who are worse at math. This led our team to suspect that math-proficient people would compare incomes more, too. Our results seem to show just that.

Simply put, the better a person was at math, the more they cared about how much money they make. People who are better at math had the highest life satisfaction when they had high incomes. But deriving satisfaction from income goes both ways. These people also had the lowest life satisfaction when they had lower incomes. Among people who aren’t as good at math, income didn’t relate to satisfaction nearly as much. Thus, the same income was valued differently depending on a person’s math skills.

Money does buy happiness for some

An often-quoted fact – backed up by research – says that once a person makes around $95,000 a year, earning more money doesn’t dramatically increase satisfaction. This concept is called income satiation. Our research challenges that blanket statement.

Interestingly, the people who are best at math did not seem to show income satiation. They were more and more satisfied with more income, and there didn’t appear to be an upper limit. This did not hold true for people who weren’t as talented at math. The least math-proficient group gained more satisfaction from income only until about $50,000. After that, earning more money made little difference.

For some, money does seem to buy happiness. While more work needs to be done to really understand why, we think it may be because math-oriented people compare numbers – including incomes – to make sense of the world. And maybe that’s not always a great thing. In comparison, those who are worse at math appear to derive life satisfaction from sources other than income. So if you are feeling dissatisfied with your income, maybe seeing beyond the numbers will be a winning strategy for you.![]()

Pär Bjälkebring, Assistant Professor of Psychology, University of Gothenburg and Ellen Peters, Director, Center for Science Communication Research, University of Oregon

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.